As the seasons change, so does the narrator’s grip on the past. Once haunted by memories of Marlène, they slowly learn to coexist with her ghost, and to embrace the fleeting beauty of life. Through music, conversations with strangers, and nights spent dreaming of revolution, they discover that meaning isn’t found—it’s created.

Author: Elsa Godinho de Matos

Spring

Part 4 of 4

From then on, time accelerated. The snow had melted, little buds bravely spread over the trees’ branches like warm kisses on a skeletal hand. Outside, people smiled and wore colourful clothes, the streets smelled of freshly baked loaves, of hope. The birds were singing. Mornings once spent rotting in bed were now slow and lingering, book in hand until the sun stroked my face. I opened the windows with every sunrise, breathing in the crisp air, aware that with every breeze that entered the room, Marlène disappeared a little bit more. I no longer held her ghost hostage behind my eyelids or under my bed, neither did I haunt it until it hid at the back of my closet, drowning in my misery. It lived in my home with me, hesitant to move out and persisting a little bit longer, keeping a low profile. We mostly left each other in peace, allowing each other to slowly forgive and move on. When we occasionally ran into each other, we smiled awkwardly yet kindly, acknowledging each other’s presence without wishing to pursue a conversation, and I quickly hurried to another room free of bittersweet memories. I was in my own home, and I refused to keep shrinking myself to make room for the past. I sought to grow towards the future.

I started putting my favourite records on in the morning, as I got ready. I replaced the slow and regretful ballads and lingering vocals with rapid and sunny beats, smiling as I realised I was dancing. I’d hum the month’s hit songs while cooking breakfast and waving my neighbours good morning. On my way to school or work, I listened to strangers’ conversations, lost in what their existences looked like to me, trying to understand what life was. People rushed home or to the office, running towards the day they could start living. They didn’t realise – or perhaps they did, but didn’t want to accept it – that this was all life was. That things they put off — saying “I’ll do it later”, or “when I have time”– are things lost. They wouldn’t get more time: they were constantly losing it. Life flies by. I thought that by watching those strangers trying their best to make the most out of it, I would live a little bit more than most. And while I saw people laughing and diving into the eyes of their lover, soaking in every second of being, I also watched tired, wrinkled faces, simply wishing to make it to the next day. I craved to meet every desperate stranger, to listen to their story and hold their hand, tell them to hang in there, it would be okay. I was the living proof of it.

Nevertheless, I still wondered what the meaning of life was. If our lifetime was finite and our goals unreachable, why were we all here on this Earth? What are we meant to do? The odds of life are so slight, and the universe so unlimited, that it all seemed rather unreal and irrelevant. Humanity craves to live, but it doesn’t know why, so it invents a deeper meaning, creates all sorts of divinities to reach for. It fights to survive, to make a sense out of breathing, and when it reaches the end, there’s merely a sour disappointment, the wish you’d done more, and no afterlife. A few decades later, all memory of you has vanished, and so have you. We all become nothing in the end.

Strangely, this nihilist philosophy did not despair me like it would’ve months ago. Life was pointless, I was doomed. I could work with that. I liked to think that when I died, I’d become stardust; that in a way, I already was. I was here, alive, my atoms eternal and intrinsically part of the universe. I existed, even if ephemerally, and I was determined to make this experience worth it. Life boiling in my veins, I’d rush to where the future was, getting as much as possible done, reading as many books, drawing as many pictures, learning as much as I could. I wasn’t much better than everyone else – I too was a victim of Death’s lingering shadow – but at least I had the privilege of awareness, and I was free. I remembered to laugh and love, to be happy. The future was mine, however short it was.

I had a small job as a tutor for a high school student; we spent hours sitting at his living room table. I could feel his parents’ gaze through the glass doors, watching us write down numbers until his vision blurred and his throat tightened. I kept scribbling, pretending not to see his disarray, reminding myself to loosen my grip around the pencil. I didn’t want to trouble him even further, was scared to embarrass him if I acknowledged his struggles. I kept my focus on the books spread on the table, trying not to think about the cold and unempathetic nature of man, or about how long it had existed. I wished science did not matter as much, or that it were used to give people more time to dream and create. I wanted him to grow up in a world that would let him do what he loved. I craved to tell him how small humanity was, how nothing would matter in a few years, that wealth was an illusion, and perhaps it was worth it to give it all up for a dream. Thousands of ideas were burning in my mind, yet I could not form a single sentence. How do you explain life to a teenager you barely know, when you yourself have barely lived?

I never told him anything. I taught him to integrate and demonstrate, to fit the system and become grey and lifeless. I taught him to hide his emotions, particularly the negative ones, and to keep them inside as they scraped and scratched the insides of his gut. With me, he learned mathematics and its cold, formal way of viewing the world, with a logical, obvious and immediate answer to every question. He was a poet, and I trapped him in a scientist’s mind.

Eventually, his parents fired me. “We need better results”, they said. I didn’t know how to tell them that no number of lessons could turn their son into someone he was not. I took the envelope with the cash they offered me and left, quietly closing the door behind me.

I decided not to search for another job, using this newly found liberty to reach out to people. I called my old friends, grabbed a coffee or two with them, apologised for disappearing. Some hastily sipped their drink, anxious to walk out the door and go back to the lives they had slowly built after I started declining invitations. But for others, it wasn’t too late. They listened closely, eyes locked with mine, hands wrapped around the steaming mug, drinking my stories and angelically accepting my excuses. By the time they took the last cold sip, we were laughing again, like life-long friends, glad to be back to ourselves after this long parenthesis.

They introduced me to new people, and as my name was tossed around in conversations spread out over circular café tables, it gained a new meaning, and I felt part of something. We discussed new literary modes, political affairs and the state of the world; everyone had an opinion about everything, radical thoughts and fresh perspectives. The world was ours to change, ideas on how we’d save it sparked as the beer caps rang on the table. I’d listen attentively, finding the faults in their theories, the genius in a solitary comment, participating, contradicting, and defending. Sometimes I stopped, going quiet for a bit as I soaked in the moment, remembering how simple it was to exist in a room full of people.

We talked of articles we could publish, protests we should go to, books to read and underground bars to try out. We were going to do something meaningful; we were a part of the inevitable shift in perspective humanity would have. We’d fix the mess our parents’ generation had made, create a better world to live in. Drink in hand, knowledge gleaming in our eyes and laughter tinting the air, everything was possible. Then someone would point out, either timidly or aggressively, that we were, after all, no better than any other generation, no different than the group older men sitting at next table, playing cards and smoking, laughing at us. All young people have hope running in their veins. Never once did they despair, and never once were they not criticised by their predecessors. Every youth craves to fix the mess they grew up in, and in a way they all do. But that glory is a short time soon forgotten, erased by waves of fresher, stronger and brighter hopes. The legacy that would take us so long to build, the impact we were supposed to make, it would vanish before we even reached the grave. We would see it turn rotten, deemed old-fashioned and conservative. It depressed us to think we’d one day be like our parents; that our children would think us closed-minded, and our values the wrong ones. How could we, the epitome of modernity, ever be despised for our thoughts belonging to another time? Right when we started to think it was all pointless, that time would undo everything, someone would say, “We’ll be different”, we’d be the first to actually leave a mark. And we went back to dreaming.

Walking back home in the middle of the night, laughter and shouts still resonating in my mind, I sometimes thought of Marlène. I lovingly recalled the time we danced under the moonlight, how she’d brush her hand against mine on our walks in the park. I remembered our fights too, slammed doors and muffled cries so as not to worry the neighbours. A sweet melancholy took over me, leaving no more room for regret and anger, or any of those sour and lethal feelings. I decided not to spend my time resenting her. I did not love her anymore, yet every day, I lived.

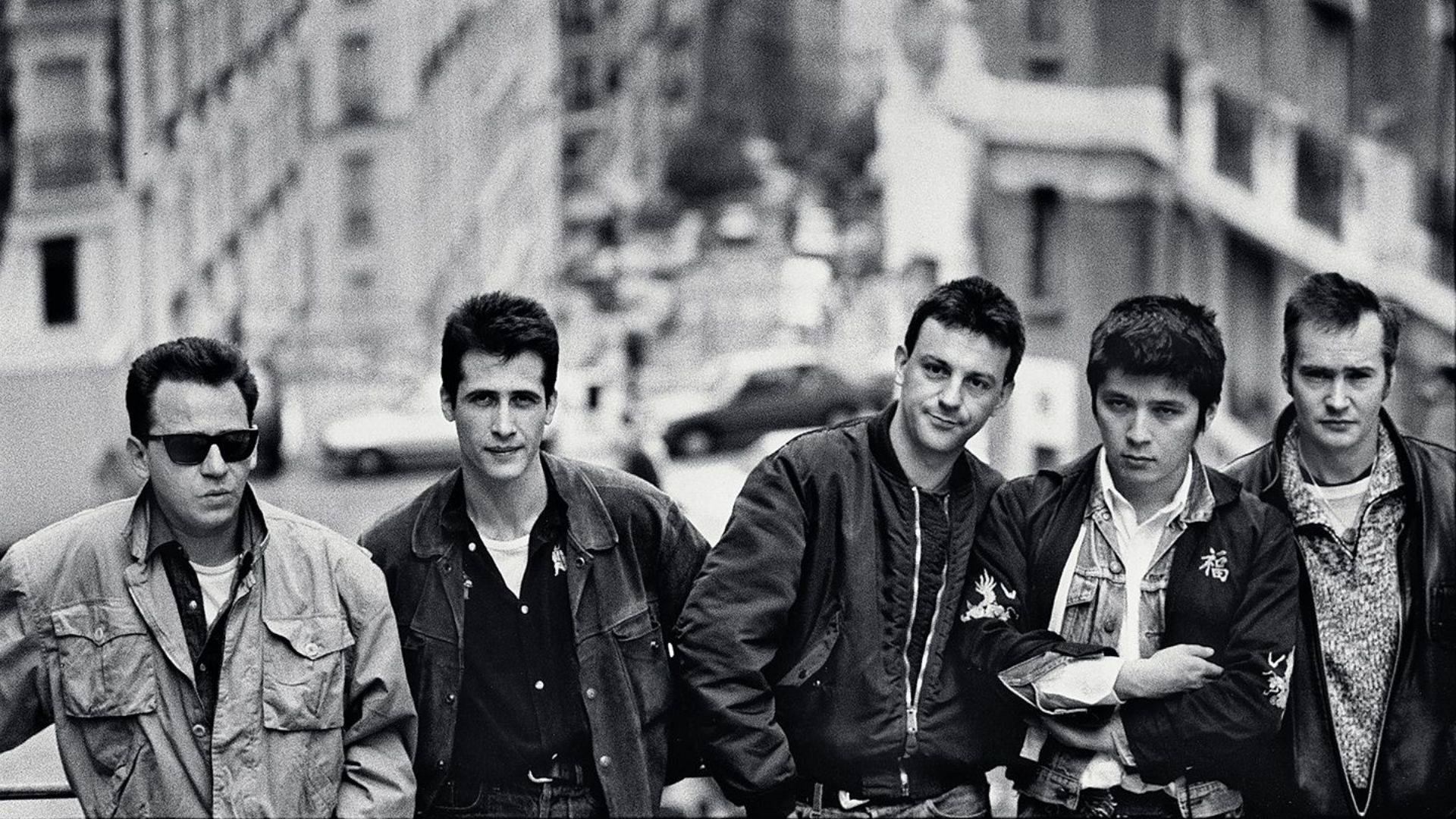

Cover Image: nennieinszweidrei from pixabay

Editor: Hedvig Paulander