The narrator is alone, adrift in their empty apartment, a mausoleum of memories. The ghost of lost love lingers in every unchanged corner, intensifying their grief. Mundane objects—plants, books, a buried cigarette—become vessels of painful reflection. As they sift through recollections, love and guilt are re-evaluated, fueling a desperate longing to be understood and seen.

Author: Elsa Godinho de Matos

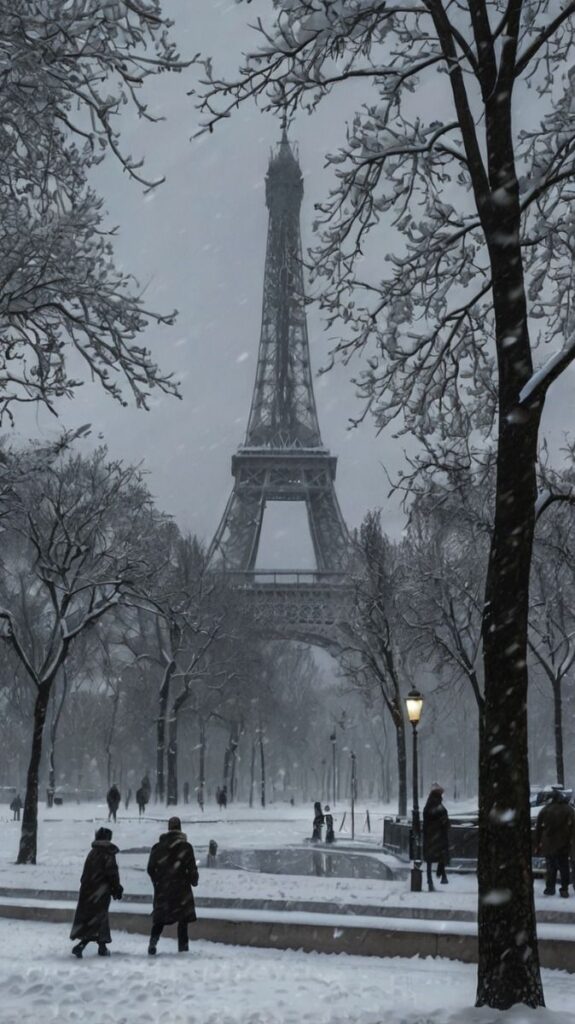

Winter

Part 3 of 4

I went home.

I went home to my empty apartment. It was not emptier than before Marlène. The couch lay on the same spot, under the window, the right side was still deformed from all the times I had sat there. Plants were scattered all over the place. Books were piled up next to the full shelves. The sink hadn’t moved. Neither had the fridge. The fruit basket was still on the counter. The phone was still resting on a chair. I hadn’t moved the rug my mom had given me for Christmas, years ago.

Nothing had changed. But everything felt different. Everything had changed.

Marlène’s body was imprinted on the left side of my couch. In another life she was still there, reading philosophy, stopping occasionally to look outside, not ever finding what she was looking for. The plants that used to thrive under my care now crawled on the floor, begging for water and attention. If I looked very closely, I would find the last cigarette Marlène had smoked in this apartment, half buried in the dry soil. Someday, I would pick it up and place it in a box, along with the letters she gave me. Someday, I’d read them. For now, I’d read the books on the floor, unopened gifts from her. They piled up like the dishes in the sink. The fridge was empty, the fruit basket had become a home for flies and worms. The phone waited patiently on its chair, untouched for days. Next to it, on my mother’s rug, was a coffee stain. I never drank coffee.

Everything had changed. Marlène was everywhere, yet she was nowhere to be seen. I would have to carry her around like a ghost only I could see, like an untold story burning and aching, deep in my stomach. She would be an unfinished manuscript, lonely in a dark forgotten drawer.

One day, I knew it, I would have to take the pictures off the wall and accept that my lover would never gaze upon me again. I would have to open every closet, every drawer, every cupboard, hoping to find something that belonged to her, dreading to find that she had carefully, methodically removed herself from my life. I would have to throw the rotten life away, open the windows and let the wind wash the taste of heartache away. One day, I would have to change my bedsheets, losing her scent for the very last time.

The day would come when I would pick up that goddamn cigarette butt. I’d open the box with all her letters, read the words of love, and in between her poetry and metaphors, in between her heartfelt and passionate declarations, I would find Marlène’s despair to be loved as she loved me. I would see in her passion all that I did not give her, all that was missing. I would find that the oranges I peeled for her meant nothing when compared to her words, that the way I braided her hair and cooked her favourite dish would never be enough for her. I would understand that Marlène did not know how to see my love in all the things I did for her. That, in the same way that I did not read her letters because all I wanted was breakfast in bed, she barely touched the coffee I made despite my disdain for it, because all she wanted was an “I love you”.

That day, sitting with the box on my lap, I would hear Marlène’s screams, her voice breaking and begging for love. “Tell me you love me, show me you care, get down on your fucking knees and tell me you wouldn’t want to be with anyone else in the world”. I would remember my silence, standing there like a ghost, not knowing how to pronounce those three simple words. I would see her tears, her desperate rage, see her fall to the ground, recall her words, dropped like a death sentence: “Every day that I love you is a day that I die”.

And suddenly, everything would fall into place, all would make sense. Sitting there on the wooden floor, a bottle of wine in one hand, Marlène in the other, I’d understand. Utterly aware of my surroundings, of every particle dancing through space, I’d know why it had all happened. And then, as furtively as it had come, the epiphany would be gone. I’d go back to ignorance, to contentment. It is safer there: the more you know, the more you wish you could forget.

I spent my days the way I felt I would spend my future: in a foggy numbness, falling in love with strangers in fever dreams, only to wake to an empty bed and a silent phone. I focused deeply on my studies, redirecting my grief towards stars I would never visit, pretending my insomnias were caused by math problems and not equations of the heart, mingling heartache with headache. I fixed all my problems with caffeine, anxiously yearning for a scent of the past. I woke up with the sun or went to sleep when the moon disappeared. It made no difference after all; night followed day in a dim monotony. I couldn’t allow myself to have a single second to breathe, did not dare to, for as soon as I closed my textbooks, Marlène’s accusation lingered in my mind: “Every day that I love you is a day that I die”. Recalling the emptiness on her darkened face—that desperate look of resignation—I’d crumble like the of ink-covered pieces of paper I tossed violently against the wall. I could not find the answers that mattered, not even in the most complex numbers.

But then some days I’d wake up as if struck by lightning, crushed once again by the magnitude of understanding. Like that day I had picked up the box where Marlène spent her days, I’d know why it had all happened. I’d see how terribly guilty I was, I’d want me dead for the monster that lived in me. How dared I be alive?

When the guilt became so unbearable I felt like throwing up, when existing seemed intolerable, I’d scribble some words in the margins of an old notebook, in red ink. I knew then why newborns wail as they take their first breath. They must feel, when the oxygen burns their lungs, how terrible it is to be alive. And I knew, too, why Marlène was a poet. How sometimes, the pain is so excruciating it makes you spit blood and mucus and bile on a page until it’s as dirty as you are. The white cleanness soiled, like a weeping, dying creature.

On mornings like that, I crawled out of bed and dragged myself to the bathroom, staring at my reflection in the mirror. I had never felt this empty, faded, and cold before. I’d look at Marlène’s ghost in the eyes and shivered under her hateful gaze, grieving the joy I had lost, staring at the hole in my chest, left by the long-gone faith. I’d stay there for hours, picking myself apart. No one would notice my absence anyway. My name had become cold and meaningless as it forgot the touch of lips.

And when I was sinking so low I was certain I’d drown, then came the fire. It started in my clenched jaw or my trembling fingers, spread to my whole body like a plague, possessed me with a madness I was afraid of. It burnt me to ashes until I dig my nails under my skin and watched it redden, recognising Marlène’s tears in the blood escaping from my body. But blood stains and lingers, and I would have rather had a scarlet red home than the absence of my disappeared lover. I pressed harder in frustration, wishing she could bear half my guilt, half the blame she had left me with. In that moment, I prayed I could go back in time, to that cursed night I had followed her out of the club, leaving my friends and life behind. I would have given everything to be laughing at a coffee shop again, instead of bleeding on my bathroom’s floor. She had made me as sick as her, why didn’t I get to stand behind her and watch her quiver under my anger?

I couldn’t take it anymore. I grabbed my coat and stepped outside, the cold biting me as I tightened my grip around Marlène’s box. I walked until I could not recognise any of the shops or streets anymore, looking for her in every stranger. Only when I was completely lost did I stop and leave the box next to a full public bin. I walked a bit longer, resisting the urge to go back to those familiar memories I had abandoned, to save them from such a grotesque death. All the words, the photographs, cinema tickets and coffee shop receipts, next to remains of food in tin cans, diapers and empty bottles.

After a while, I let myself fall on a park bench, bringing my legs to chest, wrapping my arms around them. It started snowing. The flakes danced around me, falling on my clothes, crystallising on my lashes. I wondered if my tears would freeze. I felt like a grown-up child who didn’t fit in their mother’s lap anymore.

When it stopped snowing, the night had settled. I checked my watch; it was only six in the afternoon. I was so cold that I couldn’t focus on anything else. Or maybe there was nothing left to focus on. I had cried all the tears I had in me and was so thirsty for peace I could’ve drunk the snow. But its greyish colour reminded me of myself. I didn’t feel real. I watched myself from above, slumped on a frozen park bench. Who was this person?

I looked around. I noticed all the people walking around, and I saw them as they were for the first time. Right then and there, they existed for themselves, not just as a pale copy of Marlène. I saw a girl holding her mother’s hand, eating her goûter: a piece of baguette with butter and dark chocolate. Would the mother one day stand outside her daughter’s room, listening to her silent sobs, unable to open the door? And that ageing man I could see through a window from the building across the street, whose anger was real and loud? Had he married the love of his life or the first woman that would settle for him? Had his kids promised to be different, only to turn out like him? There was boy, too, in those cursed early teen years, staring at the footsteps he drew in the snow. Had his friends been there, would he have ignored the snow’s magic? He passed by an elderly couple, the man holding a cane, the woman dragging a cadis, both disappearing behind layers of clothes. They were holding each other’s gloved hand. “I hope they’re here next year”, I thought. It must mean I wanted to be there too, to see them.

I got up and found my way back to my apartment. I bought a pain au chocolat on the way, let the melted chocolate warm me up from the inside, and smiled at the cashier. As I was stepping out of the bakery, I noticed a paper taped to the glass door. A handwritten note in blue ink informed the clients that the shop would be closed for a few days in March, next week. I stopped halfway through the door, reading the sign repeatedly, unable to understand. March was next week.

Edited by: Hedvig Paulander